This article is in the Beyond The Secret Garden Category

Beyond the Secret Garden? ‘We English’: Nonfiction and Belonging in Children’s Literature

In the latest in their Beyond the Secret Garden feature, Darren Chetty and Karen Sands-O’Connor’s consider representations of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic voices in reference books for children.

‘The races of men found on the earth are many in number. But they may be reduced to three, namely, White men, Black men, and Tawny men. We English belong to the White race of men.’ (112; The Holborn Series Geographical Reader No. 2: Geographical Terms. London: Educational Supply Company, 1899.)

Following the 1870 Elementary Education Act, British publishers began expanding textbook production to include subjects now required for certain groups of (and eventually all) British primary students; one of these subjects was geography. In the UK, this was not only a study of physical land and climate features, but also focused on people, culture, and economics—particularly of the British Empire. The geography quoted above was typical of the discussion of differences between people; initially based on skin color only, the differences quickly expand to the ‘uses’ of different groups of people. The Holborn reader suggests that the skin of Black men allows them to ‘carry on certain employments which it would be hard to carry on without them’ (110), such as sugar cane and cotton production. ‘This is because they are able to bear the hot tropical sun, when white men would die under it’ (110).

Seventy years later, these claims were still common in children’s geographies. The 1969 reference book Family of Man had Lady Plowden on its editorial board. Plowden’s report on education had, in 1967, suggested that children’s books in schools be re-evaluated for ‘out of date attitudes towards foreigners, coloured people, and even coloured dolls’ (71). However, Family of Man includes a discussion of the three race theory. Family of Man labels the three races ‘Mongoloids, Negroids, and Caucasoids’ (11) and states that ‘In the hot climate of Africa people with dark brown skins, dark eyes and thick wooly dark brown hair usually lived longest’ because ‘They were better protected against the burning sun’ (12).

Usborne published a similar reference book, entitled Peoples of the World; it is interesting that the 1978 and 1990 versions of the book contains the racial separation (they include four races, adding the Australoid race), but a 2001 version, completely revamped, says only, ‘Sometimes differences in appearance can help you recognize where a person might be from. But people have been moving around, or migrating, for thousands of years, so most countries have many different types of people’ (7).

Family of Man also goes on to define different groups, religions, and historical periods connected with movement of and change in people. The section on ‘West Indians’ suggests that ‘settlers began to buy Negro slaves’ (54). No mention is made of the settlers’ origins, but the next paragraph, which opens, ‘Then European families came from Spain, France and Britain’ to the West Indies (54) elides British involvement in slavery. The end of the section argues, ‘There are too few jobs for people in the West Indies and so many have been forced to leave their homes and find work in other lands. Many West Indians have settled in English-speaking countries, such as Britain’ (54). This passage not only excuses the white British from involvement in slavery, it completely erases the unequal connection between Britain and its (former) colonies. This makes the West Indies both responsible for its own demise (‘not enough jobs’ apparently has nothing to do with British underdevelopment of the region) and also dependent on Britain to save them (but only because they speak English).

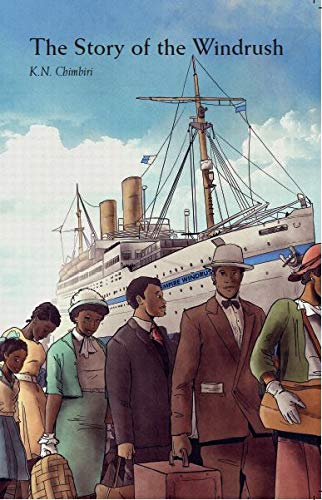

It is easy to forget that until recently, the idea of the Windrush generation was not a phrase in common parlance. A close look at two books published just four years apart, reveals significant variation, not only as to what parts of history are told, but also how history is written for children. The Empire Windrush by Clive Gifford was published in 2014 as part of the Big Cat reading scheme. The Story of the Windrush by K.N. Chimbiri was published in 2018 through the author’s own publishing company, Golden Destiny.

There are subtle, yet important differences in how each book contextualises the story of ‘The Empire Windrush’ arriving at Tilbury Docks in 1948. Whereas Chimbiri’s book includes reference to London Transport and the National Health Service advertising for staff in the Caribbean, Gifford’s text reads, ‘From 1948, the UK government allowed people living in places that it ruled, including the West Indies, to move to Britain’ (6). ‘Allowed’ is a curious word, suggesting benevolence on the part of Britain, rather than a war-torn nation in need of West Indian assistance.

Whilst both books refer to how Britain was viewed by many who travelled on the Empire Windrush in 1948 as the ‘Mother Country’, they differ in the context they provide in order for children to understand this idea. For Gifford, affinity with Britain is explained by speaking English and hearing British news on the radio. Chimbiri includes information on the many West Indians who served in the British army in World War II. Gifford refers to the West Indies as being ‘ruled by Britain’ and provides a map of the Caribbean region whereas Chimbiri places this in the context of the British Empire, offering a map of the Empire as well as one of the region. She notes ‘Most people in the Caribbean were of African descent; however in school the students were taught little about Africa or the Caribbean. Instead the focus was on England and English history.’ (9) Gifford limits his information on the education system in the Caribbean to ‘Schools were strict and teachers were treated with respect’. (5) and that children read British books.

Both books avoid the topics of the enslavement of African people and indentured servitude, which are important for understanding the population in the Caribbean islands. Chimbiri does however begin her section on the islands with information about the diversity of peoples on the islands. Gifford does not address this but rather discusses the climate, the crops that grow and how the islands are popular with tourists. These comments suggest a particular point of view – a greater emphasis is placed on the utility of the islands. This is in keeping with how the islands were viewed by the British Empire. However Chimbiri places the people of the Caribbean front and centre in her telling of history – indeed they are in the foreground of the cover, with the ship, which takes up the entirety of the cover for Gifford’s book, in the background. We suggest this is fitting. The Windrush story is social history. Chimbiri’s book clearly recognises this, at various points picking up the story of Sam King and offering us Black protagonists. Gifford acknowledges King becoming Mayor of Southwark. Chimbiri impresses upon us the pioneer status of The Windrush Generation (whilst acknowledging the prior Black presence in Britain); she states that King was the first Black Mayor of Southwark.

However Chimbiri also stresses that whilst most of the travellers on the Empire Windrush were Black, not all were. She includes the 66 Polish people who boarded the vessel in Mexico, and the Indian Caribbean people who made the journey in her telling of history. Both books have almost exactly the same number of images depicting people – yet whilst Gifford’s book includes only three with white people depicted, Chimbiri’s includes ten, demonstrating that 20th century Black history is intertwined with British history, not isolated from it.

Chimbiri connects recent history with the present when she writes that the people of the Windrush generation are the ‘foreparents of many of today’s Black British people’ (35). This attention to terminology (elsewhere she uses ‘people from the Caribbean’ and ‘African-Caribbean’) and its relationship to nationality and identity is less apparent in Gifford’s’ book, where he writes ‘Today, around 600,000 West Indians live in Britain and work in many different jobs including business, medicine, education, sport and music’ (27). Most of the 600,000 are not, in fact, West Indians at all, but British-born citizens. It suggests, most probably unintentionally, that ‘we English’ are still white, and if you are Black, you cannot count among the British.

The Story of the Windrush by K.N. Chimbiri is published by Golden Destiny, 978-0956252500, £6.99 pbk

Karen Sands-O’Connor is professor of English at SUNY Buffalo State in New York. She has, as Leverhulme Visiting Professor at Newcastle University, worked with Seven Stories, the National Centre for the Children’s Book, and has recently published Children’s Publishing and Black Britain 1965-2015 (Palgrave Macmillan 2017).

Darren Chetty is a teacher, doctoral researcher and writer with research interests in education, philosophy, racism, children’s literature and hip hop culture. He is a contributor to The Good Immigrant, edited by Nikesh Shukla and published by Unbound, and tweets at @rapclassroom.

(Note: Darren Chetty is thanked in the Acknowledgements of The Story of the Windrush for offering feedback on a draft.)