This article is in the Opinion and Other Articles Categories

30 Years of Elmer, the Indispensable Elephant

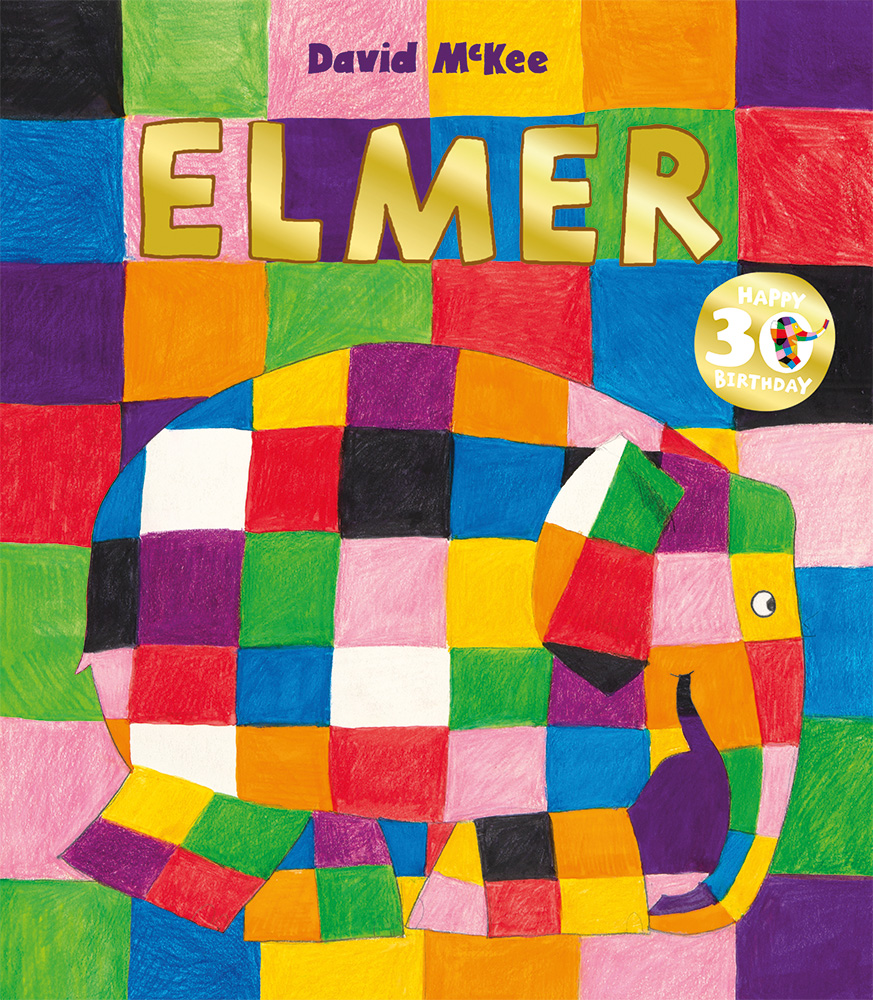

Elmer the patchwork elephant has long held a special place in many hearts. He’s a fun-loving optimist who thinks for himself, cares about others and is a dab hand at getting everyone to work together, so it’s a pleasure to see the 30thbirthday celebrations planned this year on his behalf. Carey Fluker Hunt reviews his impact.

The first book about Elmer actually appeared way back in 1968 but was republished with new artwork in 1989 by Klaus Flugge at Andersen Press, where it was soon followed by many more. There are currently 39 books in the collection and the fortieth, Elmer’s Birthday, will join them in September. But how did the idea for the first story come about?

McKee admits that aspects of Elmer are manifestations of his own personality and has talked about the family members who inspired other characters, including a ventriloquist uncle who bequeathed his skills to Elmer’s cousin Wilbur. Significantly, though, the impulse to create a multicoloured hero with mixed feelings about fitting in with the herd came in response to a racist slur hurled at his daughter in a Devon street, and although these books were not constructed as vehicles for debating ethics and morality, a story born from that encounter was always going to have an edge to it. The Elmer books are full of fun, friendship and colourful goings-on, but running through them are fundamental questions about the needs of individuals, how people should behave to one another and what kind of society we want to live in. Emotional literacy and a values-driven framework lie at the heart of these books, with themes including self-esteem and wellbeing, individuality, diversity and belonging explored throughout. As a character, Elmer demonstrates some really effective attributes and skills. Whether mediating between groups wanting to use the same river, putting two and two together about a ‘terrifying’ monster or managing the behaviour of a bunch of overexcited (and competitive) youngsters, Elmer’s calm optimism, together with an ability to think for himself, ask the right questions, listen carefully and bring everyone on board, makes him an exemplary problem-solver. Even when the difficulties seem intractable (the hunters are closing in, he’s fallen down a cliff, the rainbow’s lost its colours) Elmer never panics, and his capacity for grappling kindly, creatively and effectively with the big issues of the day make him indispensable.

McKee admits that aspects of Elmer are manifestations of his own personality and has talked about the family members who inspired other characters, including a ventriloquist uncle who bequeathed his skills to Elmer’s cousin Wilbur. Significantly, though, the impulse to create a multicoloured hero with mixed feelings about fitting in with the herd came in response to a racist slur hurled at his daughter in a Devon street, and although these books were not constructed as vehicles for debating ethics and morality, a story born from that encounter was always going to have an edge to it. The Elmer books are full of fun, friendship and colourful goings-on, but running through them are fundamental questions about the needs of individuals, how people should behave to one another and what kind of society we want to live in. Emotional literacy and a values-driven framework lie at the heart of these books, with themes including self-esteem and wellbeing, individuality, diversity and belonging explored throughout. As a character, Elmer demonstrates some really effective attributes and skills. Whether mediating between groups wanting to use the same river, putting two and two together about a ‘terrifying’ monster or managing the behaviour of a bunch of overexcited (and competitive) youngsters, Elmer’s calm optimism, together with an ability to think for himself, ask the right questions, listen carefully and bring everyone on board, makes him an exemplary problem-solver. Even when the difficulties seem intractable (the hunters are closing in, he’s fallen down a cliff, the rainbow’s lost its colours) Elmer never panics, and his capacity for grappling kindly, creatively and effectively with the big issues of the day make him indispensable.

‘What would Elmer do?’

The Guardian named Elmer an LGBTQ hero in 2014 for notching up a quarter-century of ‘opening people’s minds to accepting difference and being themselves’, an achievement he well deserves. But Elmer’s patchwork colours don’t just stand for individuality and diversity, they’re the mark of the jungle’s most effective leader, too. ‘What do you want us to do now?’ chorus the other elephants when one of the herd is stuck in a flood, and ‘What would Elmer do?’ is a question we should all ask when facing our next challenge. Elmer himself would be perplexed at his approach being held up as some kind of road map for living a better life – and one suspects David McKee might feel similarly. But however diffident he might be about Elmer as a role model, McKee admits that he likes his books to start something – ‘What I like doing is provoking discussion’ – and must be quietly satisfied to see a lifetime’s work doing just that.

Born in Devon in 1935, David McKee studied at Plymouth College of Art and began his career as an illustrator by sending cartoons to newspapers. His third and fourth books, Mr Benn, Red Knight (1967) and Elmer, The Story of a Patchwork Elephant (1968) made a significant impact on children’s publishing and in 1978 he founded King Rollo Films which brought many animations to the TV screen. With well over a hundred books to his sole credit, including Not Now, Bernard and Tusk Tusk, McKee is one of the UK’s foremost illustrators. He’s also a fine artist and painting has always been an important aspect of his life; something that’s apparent in the intricate technique he employs for his Elmer artwork, where liquid acryclic and gouache are worked into with coloured crayons and pencils to create a layered, painterly effect.

McKee’s non-naturalist approach to colour together with an interest in shape, contrast and pattern are evident throughout the Elmer books, and we don’t need to have read many of them before we feel at home in the jungle setting and begin to recognize landmarks. From the darkness of the monkey forest and the chalky whiteness of the cliffs to the tumbling waterfall and grandeur of Red Rock Pass, Elmer and friends inhabit a place possessing its own internal truth and logic, with colour as an intrinsic element. McKee has spoken of his admiration for the Fauves who used contrasting non-naturalist colours in their paintings, and there are echoes of Paul Klee’s rectangular building blocks in Elmer’s patchwork.

‘Colour has taken possession of me,’ Klee said, returning from a life-changing visit to the Mediterranean. ‘Colour and I are one.’ Elmer would definitely agree with that sentiment, and given the way his friends decorate themselves for Elmer’s Special Day would probably enjoy Miro and Matisse’s patterns, too. But then Elmer’s entire storyworld is shaped and patterned with a decorative eye. The unusual vegetation is a particular delight for those with a taste for the surreal, who may feel an urge to collect and identify these alien species, as well as admire them. It comes as no surprise to discover that one London school loved McKee’s trees so much, they asked him to paint them on the pillars of the Westway flyover.

‘Colour has taken possession of me,’ Klee said, returning from a life-changing visit to the Mediterranean. ‘Colour and I are one.’ Elmer would definitely agree with that sentiment, and given the way his friends decorate themselves for Elmer’s Special Day would probably enjoy Miro and Matisse’s patterns, too. But then Elmer’s entire storyworld is shaped and patterned with a decorative eye. The unusual vegetation is a particular delight for those with a taste for the surreal, who may feel an urge to collect and identify these alien species, as well as admire them. It comes as no surprise to discover that one London school loved McKee’s trees so much, they asked him to paint them on the pillars of the Westway flyover.

McKee deplores the way that picture books are labelled as something for the very young and likes to work for all-age audiences. The Elmer stories are fun to read and enable even the youngest children to get involved, yet taken as a body of work they have a depth and integrity that appeals to older readers, too. The values Elmer represents shine clearly and cohesively throughout these books, which have a rare power – that of embedding themselves in hearts and minds, and helping people grow. And there’s nothing remotely juvenile about that.

Carey Fluker Hunt is a writer and children’s book consultant.

Elmer’s 30th birthday celebrations include an exhibition, Elmer and Friends: The Colourful World of David McKee, currently showing at Seven Stories, the UK’s national centre for children’s books, and public sculpture trails featuring parades of decorated Elmers in Tyne and Wear, Suffolk and Devon organized by Wild in Art.