This article is in the Beyond The Secret Garden Category

Beyond the Secret Garden? England’s White and Pleasant Land

In their second article in a series looking at representations of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic voices in children’s books, Darren Chetty and Karen Sands-O’Connor venture into the fictional gardens and the countryside of children’s literature.

In Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden (1911), sickly child Mary Lennox leaves India, depicted as a place of disease and danger, for her uncle’s English manor. Before departing, she stays with an English family in India. The children take an instant dislike to her and call her ‘Mistress Mary, quite contrary’ chanting a version of the 18th century nursery rhyme. At Misslethwaite Manor, Mary discovers a walled garden. As she cultivates the neglected garden, she cultivates herself and her cousin as well into healthfulness and cheerfulness. The garden, in short, civilises Mary.

Plenty has been said of the symbolism of gardens in children’s stories. They can be read as places of nurture, health and vitality, and of human mastery over nature. Connotations with Eden abound. And as Phillip Pullman points out in Daemon Voices, the garden is a place of safety; all the more so, presumably, when entrance is restricted to a few. British children’s books have grappled with the idea of entrance into the garden, especially since the end of the second world war.

In Lucy Boston’s A Stranger at Green Knowe (1961), both the titular stranger—an African lowlands gorilla—and the boy who cares about (and eventually for) him are outsiders marked by their skin as different and imprisoned in urban England. Hanno, the gorilla, is a ‘black-faced imp’ (34) kidnapped from Africa at a young age and locked up in the London Zoo, a place that leaves animals ‘degraded as in a slum’ (38). Ping, the boy, is a Chinese war refugee living in the International Relief Society’s Intermediate Hostel for Displaced Children, ‘with vistas of concrete inside and out’ (52). Like Hanno, Ping dreams at night of the forest from which he came only to wake to the concrete jungle that is London. Both find temporary refuge in the English countryside home of Mrs. Oldknow, but neither is seen as belonging there. In the end, the authorities come to recapture Hanno, hiding in the gardens, but he charges at them and is shot. Ping tells Mrs. Oldknow that the gorilla charged on purpose: ‘That is how much he didn’t want to go back. I saw him choose’ (153). In post-war British children’s books, migrant characters were marked out as different, and in order to survive, often had to accept their assigned place in British society.

That societal place was almost exclusively the urban (and often slum) setting, even though many migrants had, like Ping or Hanno, come from rural or isolated natural settings. Locking BAME characters into urban settings also means certain plots, certain kinds of Britishness are denied them, since many of the “classic” or canonical twentieth century stories—The Secret Garden, The Wind in the Willows, The Railway Children, Winnie-the-Pooh, Swallows and Amazons, just to name a few—depend on the British countryside landscape to provide freedom and (ultimately safe) adventures for (white) child characters and readers. The countryside, in British children’s books, is a green and pleasant land indeed—but only if you are white, or accompanied by someone white.

These stereotypes are so entrenched in children’s books that David Almond, in his 2017 World Book Day offering, Island, can easily exploit them. The story is set off the coast of Northumberland (the least populated county in England), where Almond’s Syrian visitor to Lindisfarne, Hassan, stands out from the beginning. Seeing Hassan on the road, the main white character’s father says, “doesn’t look like he comes from here, does he?” (8). Later, a white woman sees Hassan and instantly mentions a London stabbing. Hassan replies, “Do you think I am one of those people? Because of Syria and my skin” (85). Almond uses the stereotype long established—that only white, English people belong to the English countryside—to question notions of belonging. But the white character, Louise, remains central in Almond’s story; she justifies Hassan’s presence to the islanders—and herself.

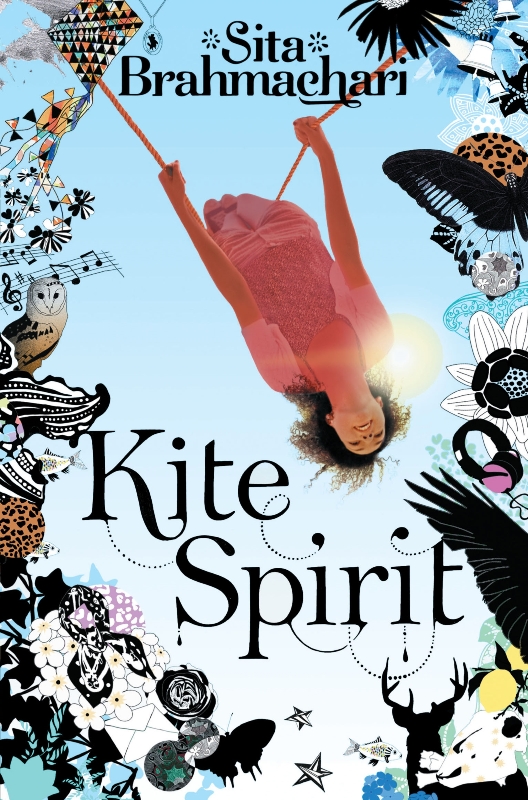

BAME authors often interrogate the proposition that BAME characters only belong in urban spaces. Unlike Almond’s Hassan, Sita Brahmachari’s mixed race character Kite, in Kite Spirit (2013), defends her own right to be in that most English of natural landscapes: the Lake District. Brahmachari begins the novel with a Wordsworth quotation, establishing quintessential Englishness, and at first, Kite feels that the Lake District “belonged to a different country and time” (104) than her. By the end of the novel, however, she can declare to a white English boy, “You know, you stared at me like this on the first day I met you . . . If it was because you thought I was a foreigner, you were wrong! It turns out I’m just as much a part of this place as you!” (307).

Recent books for younger readers have also begun opening spaces outside cities to BAME characters, but the compromises that (white) authors make to bring those characters there bear consideration. Helen Peters’ A Piglet Called Truffle (2016) is the first in an engaging middle-grade series, each of them featuring a different farm animal as cover illustration. The main human character, Jasmine Green, lives with her veterinarian mother, her farmer father and her brother Manu. Ellie Snowden’s illustrations depict Jasmine with skin darker than her friends; Peters has stated she envisaged Jasmine’s mum as British Indian and her dad as white British. The stories focus on animal rescue and it can be refreshing to have a BAME protagonist whose life-story does not include racism. Yet Jasmine never graces the covers of the books, and it feels strange that her family never mention connections to India. A pessimistic reading of these books is that silence about one’s otherness is necessary for BAME families who move to the English countryside. We wonder how (or if) children read Jasmine’s background. The series tries to normalise BAME children as part of the English countryside but does so whilst de-emphasising the BAME child’s heritage to the point of near-imperceptibility.

Picture books offer younger readers garden images in different ways. Hello Oscar (2012), part of the Zoe and Beans series by Chloë and Mick Inkpen, depicts a whole range of increasingly exotic creatures – a guinea pig, a tortoise, a chameleon, a parrot – finding their way into Zoe’s garden, before brown-skinned Oscar manages to crawl into it through a hole in the fence. The image of a brown-skinned child as the last in a line of exotic interlopers into Zoe’s garden suggests that the BAME character is still seen as an outsider. However, Anna McQuinn and Rosalind Beardshaw’s Lulu, in Lulu Loves Flowers (2017), does not need to struggle to enter a garden. With her parents’ help, she researches gardens, plants seeds, and cultivates the plants. At harvest, she invites her multiracial friends to savour the garden’s delights. The story begins with Lulu reading the poem Mary Mary Quite Contrary. As the garden grows she continually revises the nursery rhyme; she is sufficiently at home with it that she can remix it, with a Mary that looks more like her. The final page has a poem about “Lulu Lulu, extraordinary”. We see no walls around Lulu’s garden, where everyone is welcome to grow.

Picture books offer younger readers garden images in different ways. Hello Oscar (2012), part of the Zoe and Beans series by Chloë and Mick Inkpen, depicts a whole range of increasingly exotic creatures – a guinea pig, a tortoise, a chameleon, a parrot – finding their way into Zoe’s garden, before brown-skinned Oscar manages to crawl into it through a hole in the fence. The image of a brown-skinned child as the last in a line of exotic interlopers into Zoe’s garden suggests that the BAME character is still seen as an outsider. However, Anna McQuinn and Rosalind Beardshaw’s Lulu, in Lulu Loves Flowers (2017), does not need to struggle to enter a garden. With her parents’ help, she researches gardens, plants seeds, and cultivates the plants. At harvest, she invites her multiracial friends to savour the garden’s delights. The story begins with Lulu reading the poem Mary Mary Quite Contrary. As the garden grows she continually revises the nursery rhyme; she is sufficiently at home with it that she can remix it, with a Mary that looks more like her. The final page has a poem about “Lulu Lulu, extraordinary”. We see no walls around Lulu’s garden, where everyone is welcome to grow.

Karen Sands-O’Connor is professor of English at SUNY Buffalo State in New York. She has, as Leverhulme Visiting Professor at Newcastle University, worked with Seven Stories, the National Centre for the Children’s Book, and has recently published Children’s Publishing and Black Britain 1965-2015 (Palgrave Macmillan 2017).

Darren Chetty is a teacher, doctoral researcher and writer with research interests in education, philosophy, racism, children’s literature and hip hop culture. He is a contributor to The Good Immigrant, edited by Nikesh Shukla and published by Unbound, and tweets at @rapclassroom.